One man identified ‘play’ as its highest form. One woman called it ‘formalised curiosity’. Many describe it as ‘knowledge creation’. In developed nations, high quality research is indispensable. A strong economy is built upon expert insight that is transferred to government policy, business, and education. Today, the University of Malta (UoM) boasts a complex infrastructure that exposes academics to numerous funds, provides them with state-of-the-art facilities and equipment, and promotes their work in one fell swoop. But things weren’t always this way. Cassi Camilleri speaks to Pro-Rector Prof. Richard Muscat among others to uncover the leaps made over the last decade to encourage local cutting-edge research.

A university’s primary responsibility is to teach’. In a world where economies are increasingly knowledge-driven, is this statement still relevant? Most would say no. And yet, in Malta, this idea has been a major obstacle in the way of the UoM’s development for years. In an interview with newspaper Malta Today, outgoing rector Prof. Juanito Camilleri stated outright that decades ago Malta missed out on ‘major investments’ that would have seen the UoM make huge leaps towards becoming a source of research and innovation in this country. But this was not to be. And it is no secret. While other institutions across Europe were busy setting up their research infrastructure, stocking up their labs and producing critical studies ours was ‘stuck’ as an almost purely teaching institution—a problem that haunts the UoM till today.

That said, positive steps have been taken. During their terms of office, former rectors Professors Edwin Borg Costanzi, Peter Serracino Inglott, and Roger Ellul-Micallef successfully delivered a substantial number of study programmes in varying disciplines. The new paths available served the UoM well, attracting an unprecedented interest from the student body and seeing the number of yearly graduates rocket into the thousands. An important ingredient, however, remained missing.

The lacunae in postgraduate programmes, research practices, and research infrastructure were largely unaddressed. This, compounded by dwindling resources and meagre funding opportunities, continued to hold the institution back. Thankfully, things have changed since then.

‘A university without research is a secondary school,’ says Pro-rector for Research and Innovation Prof. Richard Muscat. Even when it comes to teaching at university level, ‘you have to know what is going on out there. You have to be doing your own research. Without research, you can almost forget about professing on your subject at the required level.’ But there is so much more that a university stands for, to be considered a fully-fledged one.

Echoing Camilleri’s thoughts, as expressed in his invaluable report, 2020 Vision or Optical Illusion, Muscat says that a real university is one that is integrated within the local community, producing knowledge through research and thus placing itself at the heart of government agendas. It is involved in providing the necessary material for policy that is sound and effective, benefitting the country and its people. It is also an institution that acts as a direct contributor to the economy, spawning the companies of today and tomorrow—a centre of innovation that will attract talent and business investment. It was with Prof. Juanito Camilleri’s inauguration as rector in 2006, that all of this began in earnest.

Laying down foundations

There are three things you need to undergo research, says Muscat; talented researchers doing their M.Sc.s, M.A.s, Ph.D.s, postdoctoral projects, together with research infrastructure and funds. The last decade has seen the UoM strategically ticking one box after another, laying the foundations and building up these critical ingredients. ‘We took it step by step, determining what needed to be done and what we could do, depending on the timeframe and resources,’ says Muscat, ‘and it started with the Project Support Office (PSO).’ It has been followed by the Research Infrastructure Support Unit (RIFSU) and, this year, the Research Support Services Directorate (RSSD) that will provide the academic with a one stop shop for research projects.

While other institutions across Europe were busy setting up their research infrastructure, stocking up their labs and producing critical studies ours was ‘stuck’ as an almost purely teaching institution.

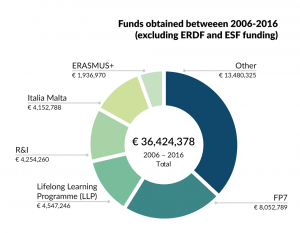

Resources for research being conducted prior to 2004 were practically non-existent. Few could run any large-scale research projects at the UoM. Upon Malta’s joining of the European Union, a new wave of funds was unleashed. Researchers wanted to make the most of their newfound opportunities and project proposals flooded into the rector’s office at an impressive rate. With no structure to organise the influx, the whole thing turned into a logistical nightmare. Faced with mountains of files on his first day as rector, all of them awaiting his signature, Camilleri swiftly began proceedings to establish the PSO.

Resources for research being conducted prior to 2004 were practically non-existent. Few could run any large-scale research projects at the UoM. Upon Malta’s joining of the European Union, a new wave of funds was unleashed. Researchers wanted to make the most of their newfound opportunities and project proposals flooded into the rector’s office at an impressive rate. With no structure to organise the influx, the whole thing turned into a logistical nightmare. Faced with mountains of files on his first day as rector, all of them awaiting his signature, Camilleri swiftly began proceedings to establish the PSO.

Now headed by Christian Bonniċi, the PSO is no longer just about streamlining the process through which research proposals would receive approval by the rector. The structure, bringing people in from the international, finance, and legal offices remains, but their responsibilities have grown, as has the team, going from just three to twenty-eight. The PSO now offers a wide range of services, including administrative and financial support, as well as advice on technical, HR, and legal aspects. In a nutshell, the organisation helps researchers build their project from the ground up and continues providing support throughout its implementation. In this way, the PSO not only strengthens individuals’ performances but also enhances the research environment of the whole University.

We took it step by step, determining what needed to be done and what we could do, depending on the timeframe and resources and it started with the Project Support Office.

With the PSO, and the organisational framework it brought with it, came a major overhaul in UoM’s laboratories—mostly EU funded. The new additions included the Biomedical Engineering laboratories, the Renewable Energy labs as well as the new Chemistry labs at Junior College. State-of-the-art equipment was also shipped in. The top-of-the-line Vicon Motion Analysis System was installed at the Biomedical Engineering Laboratory. The motion capture device, among other things, analyses gait in humans, a service which, according to Prof. Ing. Kenneth Camilleri (Centre for Biomedical Cybernetics, Faculty of Engineering) will help numerous health professionals treat Maltese patients in the not-so-distant future.

Time to grow up: A question of sustainability

Funds and resources are problematic worldwide. Science and research are expensive. Muscat brings up the example of the University’s Research Fund Committee which is allocated €500,000 per year for research. Unfortunately, that barely covers any research costs. ‘With 200 projects running per year, every researcher will receive €2,500. This is very limiting. Purchasing a few milligrams of a particular enzyme costs at least €1,000. This would last for just a few experiments. So in a few weeks, basically, my monies dry up. Obviously, we need more.’

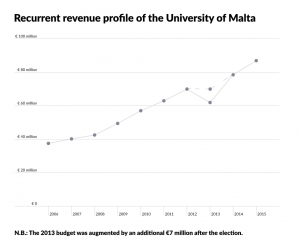

The Maltese government supports most of the UoM’s financing. It doles out millions every year to cover salaries and basic running costs. Better policies could help the UoM grow. However, the government alone cannot invest enough in the UoM. In his 2020 Vision report, Camilleri stated that investment would have needed to grow by 33% between 2011 and 2013 in order for the University to keep up with the necessary growth. In 2013 this would have meant an extra €72 million. Government did not match these needs.

Seeking to tackle the issue head on, Camilleri set up a number of entrepreneurial entities all of which work in some way, shape, or form to empower researchers and add value to their work, including that of the monetary kind.

At the top of the list is the Corporate Research and Knowledge Transfer Office (CR & KTO), responsible for establishing the UoM’s Intellectual Property Policy, which helped academics identify and protect their IPs for the first time, and TAKEOFF, the incubator that brought us MightyBox’s internationally acclaimed Posthuman board game. The next stop was the Research, Development and Innovation Trust (RIDT) which sources private investment for high quality R&D. So far, the RIDT has taken the government’s initial investment of €500,000 and doubled it; a tremendous achievement. Lastly, is the Centre for Entrepreneurship and Business Incubation (CEBI), the newest addition to the group, set up to stimulate growth of entrepreneurship across numerous industries, including science and technology, media, and the creative industries, and many more. With help from the KTO, CEBI now offers a Master programme in Knowledge-Based Entrepreneurship, a move that will help turn UoM ideas into new Maltese startups that will grow into companies working with the UoM.

‘The crux of all this, the big picture, is to have Maltese professionals, Maltese IP, and Maltese companies,’ says Muscat. ‘Having foreign investment supporting research at the UoM is positive,’ he says, but we need to be aware that ‘if all your major companies are foreign and they decide to move their business elsewhere, nothing is going to stop them.’ All the work done would end up being undermined or lost.

Asked to describe his experience working with Camilleri for the last 10 years, Muscat encapsulates it all eloquently into just one word—‘Fun’.

Camilleri has been commended for his initiatives, with representatives from each office crediting him as ‘instrumental’ in getting things off the ground. And this has translated into a real boost in research. ‘In research, the proof of the pudding is in the eating,’ says Muscat, ‘and that often relates to numbers, the academic totals and the papers they publish.’ Looking into this, the results are impressive. The total number of academics at the UoM has ‘increased over the past 10 years with some 10% from overseas.’ The same could be said for their publications. In research, the UoM has gone from publishing about 500 papers in peer-reviewed journals in 2005 to 2,500 in 2015, a tremendous leap on both counts. One in ten are published in top tier journals competing with the best institutions worldwide, which is close to the EU average. And now this work is also gaining appreciation from the general public thanks to another project Camilleri helped bring to fruition—Think magazine.

Think is yet another attempt to bring the UoM closer to the Maltese people, and a successful one at that. Think editor Dr Edward Duca (Communications & Alumni Relations Office, University of Malta) describes Camilleri as a ‘visionary and a genius’ who supported his vision for ‘drastic change’ in the way the UoM communicated with the public. Some warned that he might lose his job over the approach. However, Duca found nothing but support from the rector, leading Think to grow and become the prime publication that it is; gaining mainstream popularity being distributed at news outlets across the island and online, garnering respect beyond the islands’ shores.

Think is yet another attempt to bring the UoM closer to the Maltese people, and a successful one at that. Think editor Dr Edward Duca (Communications & Alumni Relations Office, University of Malta) describes Camilleri as a ‘visionary and a genius’ who supported his vision for ‘drastic change’ in the way the UoM communicated with the public. Some warned that he might lose his job over the approach. However, Duca found nothing but support from the rector, leading Think to grow and become the prime publication that it is; gaining mainstream popularity being distributed at news outlets across the island and online, garnering respect beyond the islands’ shores.

We’re not quite done yet

Naturally, there is plenty more that needs to be done. While these entities are now working around the clock to turn the UoM into an institution that generates a greater proportion of its income, the journey is not over yet. New revenue streams need to be found. Improving international rankings and greater marketing of the University to countries further afield would be one way of doing it, Minister Owen Bonnici wrote in a scathing article in the Times of Malta in 2011, echoing what everyone else was thinking. However, a brief analysis of that suggestion reveals this is undoubtedly a case of ‘easier said than done’.

With EU rules in place, students from member states, like local ones, are entitled to a free education. So while marketing the University is important, the institution also needs to maintain sustainable numbers of EU nationals. This situation has seen the UoM spending increasingly large sums of money marketing to students from non-EU countries like Oman, Kuwait, India, China, and the USA. It has also given rise to one of Camilleri’s most controversial propositions in his 2020 Vision report—to start charging course fees. Of course, this is nothing short of a political landmine, one that many choose to steer clear of and ignore, but education is not free and neither is research, making it an unavoidable eventuality. Now at the end of his term, Camilleri will leave this question to his successor.

‘The opening of the Life Science Park, situated next to Mater Dei Hospital, will be a major milestone for Malta. The task of the new rectorate will be to increase the number of Ph.D.s graduating annually to at least 50 and postdocs to match. This key number would allow local spin-off companies to develop,’ says Muscat. ‘Those to me are the next goals for the new rectorate, if we are to have our own life science companies.’

Asked to describe his experience working with Camilleri for the last 10 years, Muscat encapsulates it all eloquently into just one word—‘Fun’. ‘At the end of the day, this is the way we worked. He came to me with an idea. I shared my ideas and we planned a way forward. We kept each other posted. I asked for his backing 100%, he gave that to me and more, and off we went. It was a constant evolving conversation, back and forth.’

The incoming rectorate has many obstacles to overcome but, unlike 10 years ago, a solid foundation on which to build is now in place. Muscat supports the incoming rector, Prof. Alfred Vella, and his new team. It is time to ‘pass on the baton’; work will continue in earnest.

read more

- Bonnici, Owen. ‘Malta Needs a Better University.’ Times of Malta, 4 May 2011. Web.

- Laveira, Nestor. ‘Not Playing Happy Schools | Juanito Camilleri.’ MaltaToday, 22 Mar. 2011. Web.

- Camilleri, Juanito. 2020 Vision or Optical Illusion? University of Malta, 2010. Print.