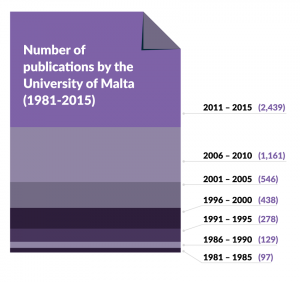

Research is progress. Without it, we would not have found cures for diseases, or solved some of the world’s problems. Thanks to the University of Malta’s shift from teaching to research, research publications have more than quadrupled since 2006. Dr Edward Duca takes a look at some of the University’s star research projects.

R

esearch helps solve the world’s problems. You need research to figure out if drugs are harmful, if a chemical can be turned into a treatment, if heavy incarceration really does reduce crime, or if certain policies work to help children achieve more in life. Research is happening worldwide. Research is happening at the University of Malta (UoM).

There has been a shift from teaching to research, as part of outgoing rector Prof. Juanito Camilleri’s vision. Research publications have more than quadrupled since 2006, a result of the big increase in the number of academics freed up by a new collective agreement in 2009. Key to their enablement was over €40 million in research funding, most of it from the EU.

And it was the Project Support Team (PST) that enabled access to this EU funding. The team helps academics find EU funding programmes, apply for them, and administer them. ‘Academics are not really interested in doing that work themselves. Our team encourages academics to get into more projects because they know they don’t need to do that [administrative] part,’ points out Alexandra Attard (Senior Manager, PST). The team reflects a change in mentality for administration at UoM.

‘When we were interviewing PST employees they had to understand that ultimately we have to provide a service,’ continues Attard. ‘“Servant leadership” is the basis upon which this project support office has been built,’ Christian Bonnici (Deputy Director, PST) states proudly. His ethos is a novel mix of mutual respect, while doing a job efficiently: ‘I need to serve you [the academic] for the most basic things while leading you to identify the right funding opportunity […]. But if I serve you then you should trust that I will lead you in the right direction.’

Crumbling under papers

When Camilleri became rector in 2006, EU projects needed his signature but he lacked advisors. There was no one specialised in EU projects, which are a unique bureaucratic monster. ‘People were getting into them but there weren’t the right support structures,’ notes Bonnici. UoM lost most funds between 2002 and 2006. By 2007, Camilleri had set up the PST, bringing together members from the International, Finance, and Legal Offices, with Bonnici joining in 2008.

When Camilleri became rector in 2006, EU projects needed his signature but he lacked advisors. There was no one specialised in EU projects, which are a unique bureaucratic monster. ‘People were getting into them but there weren’t the right support structures,’ notes Bonnici. UoM lost most funds between 2002 and 2006. By 2007, Camilleri had set up the PST, bringing together members from the International, Finance, and Legal Offices, with Bonnici joining in 2008.

Set up officially as an offshoot of the Finance Office, Bonnici, with the support of his superiors and team, then ‘beefed up the structure […] to get into the non-financial matters’. He started hiring people to provide a one-stop shop, from legal to hiring needs, for every EU application. Cleverly, PST asked academics to add its costs to EU projects, slowly growing a team with every project UoM won. The team now stands at around 30 members.

Bonnici believes that the best thing that happened to PST was an online administrative management system called AIMS. AIMS ‘was the biggest investment in research support […]. It helps prepare timesheets, finance systems, and project reporting. Although it might be unappreciated, AIMS has simplified our work [and] helped eliminate cases for ineligible funds’.

The PST also employs Ph.D. level staff, a radical move for an administrative office at the UoM. Every employee has a degree at PST. The highly qualified workforce has ‘gained a lot of confidence from the academics.’

PST has joined an EU funded COST project called BESTPRAC aimed at developing a ‘best practice in research management and administration’ between 30 different institutions around Europe.

Apart from developing benchmarks for what each PST around Europe should be achieving, ‘the group is acting as a lobbying group with the EU.’ Malta has a voice to better match EU funds with the local scenario.

Research publications have more than quadrupled since 2006, a result of the big increase in the number of academics freed up by a new collective agreement in 2009.

The Ph.D. research these employees undergo is usually work-related. So you end up with ‘a finance person specialised in research, and a procurement person specialised in research—it changes the mentality completely,’ and explains their success.

Feathers in the University’s cap

The UoM recently won one of the most prestigious funds available to academics. Dr Aaron Micallef (Department of Geosciences, Faculty of Science) was awarded €1.7 million to study how fresh water can be collected at the bottom of seas and oceans. He wants to do this by comparing waters around Malta and New Zealand.

‘This ERC grant was new for everybody. What we need to do now is see what resources are required and meet those resources,’ points out Bonnici. ERC grants ‘gauge the success of a university. Obtaining this funding was the cherry on the cake, our dream,’ affirms Attard.

The Project Support Team also employs Ph.D. level staff, a radical move for an administrative office at the UoM.

While a Maltese research project was the main recipient of this grant, it is not the only project to have received ERC funding. The FRAGSUS project, awarded funding in 2013, saw Malta involved in the largest ever local archaeological study to the tune of €2.49 million. A team of 80 people, coordinated by Prof. Caroline Malone (Queen’s University Belfast) and led in Malta by Prof. Nicholas Vella (Department of Classics of Archaeology, Faculty of Arts), are trying to figure out what wiped out an ancient civilisation—referred to as the Temple People—who built the oldest free-standing stone structures in the world. The civilisation mysteriously disappeared in 2500bc.

While a Maltese research project was the main recipient of this grant, it is not the only project to have received ERC funding. The FRAGSUS project, awarded funding in 2013, saw Malta involved in the largest ever local archaeological study to the tune of €2.49 million. A team of 80 people, coordinated by Prof. Caroline Malone (Queen’s University Belfast) and led in Malta by Prof. Nicholas Vella (Department of Classics of Archaeology, Faculty of Arts), are trying to figure out what wiped out an ancient civilisation—referred to as the Temple People—who built the oldest free-standing stone structures in the world. The civilisation mysteriously disappeared in 2500bc.

Maltese history is a rich source for academic research: the Knights of St John, the artist Caravaggio, the Baroque period, the French and British colonial era, and other topics within the Mediterranean region are all studied intensely (various departments and the Faculty of Arts). But also interested in Maltese history are geneticists. Geneticists look at the historical records within our bodies. The Maltese Genome Project (Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences) is planning to sequence 1% of the local population. Its first achievement is discovering that the Maltese population originates from 12th century Siculo-Arabic roots. The same researchers identified the KLF1 gene in Maltese families involved in the blood disorder thalassaemia. Further studies are trying to see how gene therapy and precision medicine can treat thalassaemia patients. The reference genome from the project will be used in studies from cancer to heart attacks.

Over one in three deaths in Malta are due to cardiovascular disease. A large-scale study headed by Dr Stephanie Bezzina-Wettinger (Faculty of Health Sciences) is using lifestyle and health data with genetic information to find out why. The first findings have shown the typical links between genes and lifestyle. However, the Maltese population might have a higher genetic predisposition than Europe to heart attacks, due to a higher rate of diabetes, a common risk factor. Sequencing around 1,000 participants will tease out the reasons. Another research group led by Prof. Joseph N. Grima (Faculty of Science & others from the Faculty of Medicine & Surgery) is taking a different approach. These surgeons and mathematical modellers want to prevent future heart attacks by introducing heart stents with a groundbreaking auxetic design. Auxetic materials do not shrink when stretched, so the stent (a tube that helps keep heart vessels open) would not collapse on itself. The approach should help prevent blood vessel blockage reducing heart attacks.

A separate study into diabetes by Dr Sarah Cuschieri (Faculty of Medicine & Surgery) is looking into the disease’s genetic and lifestyle links in Malta. She wants to find out which gene differences, when coupled with certain lifestyles, tend to lead to diabetes. Another highly innovative study by the Diabetes Foot Research Group (various UoM faculties and Mater Dei Hospital) is trying to develop a relatively cheap and quick way to diagnose diabetes. The group is using a thermal imaging camera to see if the temperature of the person varies from normal—an early sign that a person could be diabetic.

The University also runs breast cancer research programmes, with local scientists having identified a critical role for PP2A (protein serine/threonine phosphatase type 2A) as a possible therapy target. Kidney disease has also been earmarked as a problem that needs research solutions. For the first time in Malta, many of these projects are being funded by various NGOs (attracted by the University’s Research Trust, RIDT); civil society has clearly decided that these issues are important enough to require research solutions.

Apart from genes and diagnosing disease, other researchers are replacing or augmenting body parts. Some are using biocompatible Portland cement (the same as the one used in the construction industry, but with a few critical tweaks) for better dental implants (Faculty of Engineering, Faculty of Dental Surgery). Teeth could soon be upgraded. Others are making hip joints that last longer and are less likely to be toxic (Faculty of Engineering, Faculty of Medicine and Surgery). Nearly 150 people needed hip replacements in 2014 in Malta. Other engineers collaborating with surgeons are improving minimally invasive surgery called Laparoscopic surgery, reducing the recovery time for patients—advances that can be used the world over.

As the human body’s most complex organ, the brain can also go wrong. The newly set up Malta Neuroscience Network covers research from Alzheimer’s disease to SMA (spinal muscular atrophy). Using the fruit fly model, researchers are trying to discover if polyphenols in the Mediterranean diet can mitigate Alzheimer’s, while others are unraveling disease mechanisms for new SMA therapies. The network also uses the mouse model for stroke imaging studies, investigates medical marijuana use in epilepsy, and explores depression treatments, to name a few.

As the human body’s most complex organ, the brain can also go wrong. The newly set up Malta Neuroscience Network covers research from Alzheimer’s disease to SMA (spinal muscular atrophy). Using the fruit fly model, researchers are trying to discover if polyphenols in the Mediterranean diet can mitigate Alzheimer’s, while others are unraveling disease mechanisms for new SMA therapies. The network also uses the mouse model for stroke imaging studies, investigates medical marijuana use in epilepsy, and explores depression treatments, to name a few.

The brain is also something to be celebrated. Rather than disease, some cognitive scientists study how we remember things and make decisions. Others study how the brain understands information that changes as time passes: a frown turned into a smile, a baseball moving through space that we need to grab, or how our brain reacts to changes it hasn’t even consciously seen (Faculty of Media and Knowledge Sciences). And linguists are looking into how humans and machines can speak to each other. Maltese speaking robots might be on the way (Faculty of ICT, Institute of Linguistics). Our brains are beautiful.

By 2030, Malta might have 10,000 people with dementia. Dr Charles Scerri (Faculty of Medicine and Surgery) has just led a team that devised a National Dementia Strategy to use research to mitigate the problem. A collaboration with Perit Alexia Mercieca (Faculty for the Built Environment) is seeing dementia-friendly buildings being designed. The same faculty is collaborating with seismologists to assess the earthquake risk around Malta, to learn how earthquakes behave, and to then measure how the current stock of buildings would react. The Maltese Islands are the most built up country in the EU, with one third of the islands covered in buildings, so this study could not be more timely.

Researchers also study the seas around Malta. A team led by Prof. Patrick J. Schembri (Faculty of Science) has studied an endless list of creatures that includes fish, beautiful white coral, snails, limpets, and crabs. Through the EU-funded CoCoNet project these studies are being linked to others all around the Mediterranean, creating a patchwork of knowledge to link marine protected areas sea-wide. The seas around Malta hold other secrets. Underwater archaeologists led by Dr Timmy Gambin recently found WWII submarines, Roman trade ships, and a 2,700-year-old Phoenician merchant vessel. Some of the largest EU projects have been attracted by Prof. Aldo Drago (Faculty of Science) to study the physical oceanography of the Mediterranean Sea from surveillance and security to wave conditions and current patterns. These answer questions about anything as diverse as wave energy potential to oil spill response.

Biologists also study the plants around Malta, while others study insects (Faculty of Science, Institute of Earth Systems). Such studies are vital to identify which areas require environmental protection while safeguarding important industries like beekeeping.

Maltese honey appears to have medical properties. One of the three varieties produced locally has been shown to cure wounds with studies carried out at the University (Institute of Earth Systems, Faculty of Science, Faculty of Medicine and Surgery) in collaboration with industry experts hint at much more powerful medical properties. Other researchers are studying Maltese wine. Oenologists and engineers have set up a wine research station run on renewable energy to prove certain wine making concepts (Faculty of Engineering). From a completely different angle, food scientist Dr Vasilis Valdramidis is studying how to prepare clean food using approaches with fewer chemicals that use less water, an innovative approach that sees sound cavity bubbles used to clean food.

The UoM covers even more diverse research subjects. Researchers from the Department of English (Faculty of Arts) are studying contemporary literature and posthumanism, analysing the effect of modern technology on our lives. ICT scientists are collaborating with the particle accelerator in CERN to understand the physical matter that makes up the universe. Others are studying microelectronic devices used in smart phones, or machine learning, both of which have huge industrial applications. And large EU funds are also being obtained for aeronautics research (Faculty of Engineering, Institute of Aerospace Technologies). The Clean Sky 1/2 and Clean Flight 2 project studied air transport pollution aiming to lower it by 20–30%. Malta played a multimillion role in this transformative project.

These projects just scratch the surface of the wealth of research happening at the UoM. EU funding has enabled the above research, though some funds come from government or are self-generated by the UoM. While research output has skyrocketed, challenges still exist. ‘Academics remain heavily loaded with teaching,’ laments Bonnici. Another issue is the availability of funds specifically dedicated for research. There are no national funds supporting basic scientific research. Doctorate and postdoctorate funds run by government now exist, yet Ph.D. funds are still woefully small while the postdoc grant scheme called REACH HIGH, while a step in the right direction, has its pitfalls. Apart from this, the UoM needs an autonomous structure for it to raise more funding which it can use efficiently and strategically in research. The staff might be more enabled, but now the institution needs empowerment.