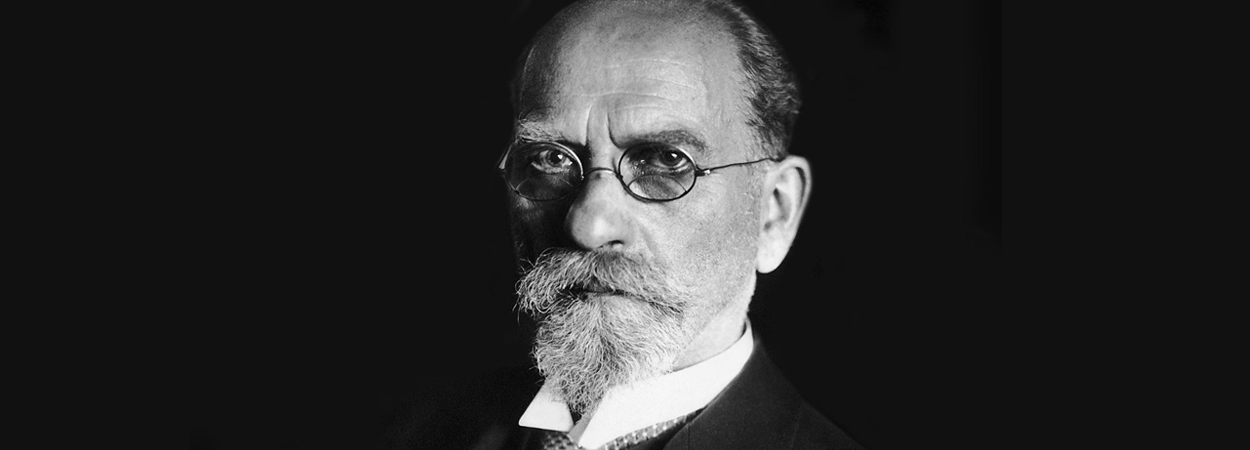

Does Philosophy need a radical beginning to overcome its perpetual crisis and finally make progress? In search of an answer in Husserl’s Phenomenology.

Dr Clive Zammit

University of Malta

In his Cartesian Meditations: An Introduction to Phenomenology (1950), Husserl sets off on his “First Meditation” with a call to: “…make a new beginning, each for himself and in himself, with the decision of philosophers who begin radically: that at first we shall put out of action all the convictions we have been accepting up to now, including all our sciences.” (p.7) As is well know, Husserl’s overarching objective for transcendental phenomenology (at least up to the publication of his Cartesian Meditations) was to establish philosophy as a rigorous science which would be built on the solid foundations of indubitable knowledge gleamed from the immanent sphere of experience to which we would gain access through the application of the transcendental epoché. It would seem that such a “radical beginning” would require that this tool for phenomenological investigation, the transcendental epoché, would therefore allow us to reach a sphere of experience which is prior to, or beyond, any historical or cultural shaping of our experience.

Is it still possible for us contemporary thinkers to aspire to this type of “pure” access to knowledge, especially in light of Derrida’s analysis of the dual ontological and nomological principles of the Arkhē, which principles both ground and lead our thinking?