By Albert Marshall

When I think back and made to recollect my memories of Oliver, a recurring overarching remembrance keeps coming to mind: that of me making Oliver laugh. Oliver spent his life too preoccupied with the world’s woes – closer home, the trials and tribulations of his own country and his fellow citizens. This left him very little time to smile and laugh. This is why I feel good when I remember Oliver being entertained by my ‘irreverent’ poetry, my unorthodox style of artistic expression in my writing, and projects for the theatre. In his critique of my work, Oliver constantly commented about the naughty child in me who hung around throughout my entire life into old age – a virtual child who makes his presence felt especially in my poetry: the linguistic games I like to play, the playful constructs of themes and concepts… Oliver managed to see through these idiosyncrasies of my writing and in the process of deconstructing these elements, he used to feel amused…entertained…and smile!

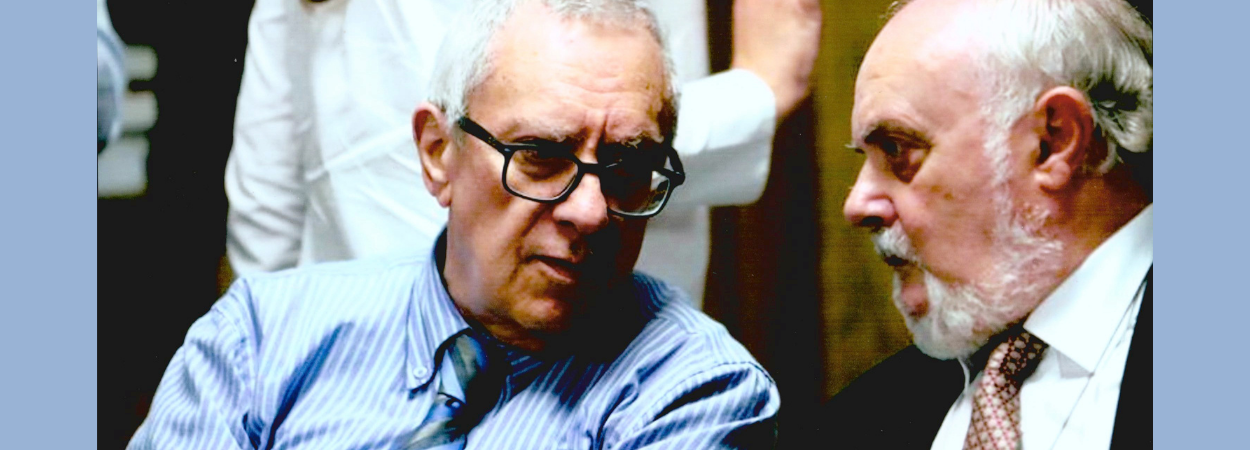

I have known Oliver since the early sixties when he and I used to share the same bench at the Archbishop’s Seminary in Floriana. Then, we both believed (or made to believe) that our vocation in life was to become priests. Eventually, Oliver married Elaine and I married Jane. I remember us having bantering conversations about possible guilt complexed for reneging on priesthood and choosing to get betrothed instead. We were great mates: a couple of nurds, I’m sure – in hindsight, I think we took our studies too seriously and missed out on the fun our classmates used to enjoy. Oliver and I used to seriously compete for the annual prizes for first-in-class: Oliver used to beat me in Maltese and I used to excel in Latin.

Two milestones that mark a solid bonding between Oliver and me later on in the sixties were the publication of an anthology of poetry (Dħaħen fl-Imħuħ, Oliver Friggieri, Albert Marshall, Ġorġ Borg, 1967) and the founding of the historic Moviment Qawmien Letterarju. Oliver was a catalyst in both projects for the promotion of literary innovation and socio-political awareness through literature at a time when the Maltese literary scene was stagnant and replete with outdated religio et patria conformities.

This bonding lasted throughout a lifespan. Outstanding features of my in memoriam of Oliver are his intellectual stamina, insatiable quest for knowledge, his innate power to teach, his aggressive stance in favour of the cultivation of a true cultural and national identity, and his reconciliatory attempts at engaging in a constant struggle against tribalized mindsets of fellow citizens and their political and parochial leaders.

Oliver’s death has taught me how untrue is the belief that such departures truncate relationships: I feel closer now to the guy more than ever before.