tTEarly in the morning, before the sun rises, birdsong fills the dewy air and the campus comes to life with students slowly starting to trickle from into their lecture halls from every corner, I like getting to the office at the Old Humanities Building, making a cup of tea, and pacing through the building. It is where I used to be required to submit my assignments back when I was a student. I must admit, it isn’t much of a sight, and more of an expression of my desire to go back in time, as most of the offices would still be closed, with silence still draping the area.

The only source of light in the corridor of the first floor, dancing on the surrounding walls, would be coming through Room 249, Prof. Friggieri’s office.

I never dared to knock. I was quite scared of how I wouldn’t be able to hold a conversation with someone of his stature, but I always wondered why his door was kept ajar.

Just a few weeks after I last saw him, through my window, making his way into the office, I heard of his passing. Even I, who was never his student, felt like things wouldn’t be the same again, let alone all those he mentored, befriended and worked with over the years.

The University of Malta community suffered a great loss, and many would find it hard to heal quickly from this. Just the sheer volume of his work, and the value of his contributions to Maltese literature, make this loss monumental.

Imut poeta u warajh iħalli xkora ta’ sentimenti (A poet dies and he leaves behind him a sack of emotions), his own haiku said.

On behalf of Newspoint, and perhaps because I was a little bit jealous of those who had experienced his genius closer than I did, I reached out to a mentee, a colleague and a friend of Oliver’s, to show our audience how much of a truth this was.

Marilyn, a mentee of Prof. Friggieri, told us it was a blessing to know him as a lecturer and then as her thesis tutor. She chose him as the latter because she wanted to explore the Gospel of St Matthew, and he had profound knowledge of both the Maltese language and Catholic teachings.

“Through this experience, there came a time when I thought the road was too long and was about to give up, but he used to encourage me to keep going, and that gave me hope. Other than the poet and professor that others used to see him as, to me he was a devoted Catholic who evangelised his students in silence.”

She recalls one particular email, in which he shared some musings on death itself.

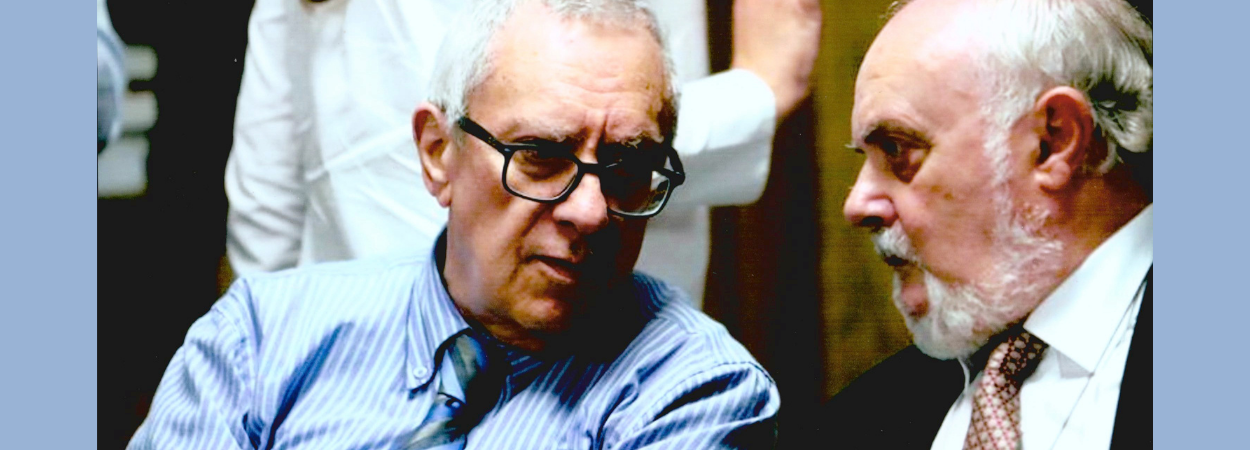

Prof. Joe Friggieri, his cousin and colleague, was one of the people for whom the door was not just ajar, but always swung wide open. Joe remembers how he and Oliver talked about everything under the sun.

“In the long years we spent together at the University, Oliver used to come up to my room to give me signed copies of his publications, though I always felt that the real reason why he came was because he wanted to talk. Oliver loved conversation, and he would talk about anything and everything, in his dry, staccato sentences punctuated by fine humour.”

Prof. Joe Friggieri also reminisces on how, a few years after they had talked about someone who impacted Oliver, he would ‘meet them again’ in Oliver's books.

“Oliver’s output as a writer was simply prodigious. He never stopped writing. My favourite book by him is Fjuri li ma jinxfux (Flowers that don’t wilt), his memoirs spanning the years 1955-1990. It’s almost 700 pages long, but a real page-turner, full of vivid descriptions of characters from all walks of life, who left an indelible mark on Oliver’s memory and feature, suitably disguised, in some of his works.”

Albert Marshall, another well-known author and a member of Moviment Qawmien Letterarju, told me about the recurring overarching memories of making Oliver laugh.

“Oliver spent his life too preoccupied with the world’s woes – closer home, the trials and tribulations of his own country and his fellow citizens. This left him very little time to smile and laugh. This is why I feel good when I remember Oliver being entertained by my ‘irreverent’ poetry, my unorthodox style of artistic expression in my writing, and projects for the theatre. “

Mr Marshall knew Oliver from the early sixties, when they used to share the same school desk at the Archbishop’s Seminary in Floriana.

“At the time, we both believed that our vocation in life was to become priests. Eventually, Oliver married Elaine and I married Jane. I remember us having bantering conversations about possible guilt complexes for reneging on priesthood and choosing to get betrothed instead.”

But in the bond that lasted through a lifetime, what stands out are “his intellectual stamina, insatiable quest for knowledge, his innate power to teach, his aggressive stance in favour of the cultivation of a true cultural and national identity, and his reconciliatory attempts at engaging in a constant struggle against tribalized mindsets of fellow citizens and their political and parochial leaders.”

And in the same way he let so many into his office, his classroom, his home and his favourite spots – because he was rarely seen by himself, I’m sure he touched the heart of all those who encountered his works in their studies, leisure time or even purely by chance.

This morning, the door to Room 249 was tightly closed.

But I hope that this piece, and the many conversations like it that will be had about you in the future, will keep your memory alive.

Thank you, Prof.

Stephanie Buttigieg